CRUISING YACHTSMANOctober 1982 by Jack Somer

Prince Edward IslandCanada's smallest province —"The fairest land 'tis possible to see"Whether Jacques Cartier actually spoke those immortal words, or if they — as so many immortal words — are apocryphal, it matters little. Prince Edward Island, in 1534, was a precious jewel in the maritime wilderness of America's northeast corner, and Cartier recognized that fact; and by some miracle, PEI remains the fairest land in those provinces. |

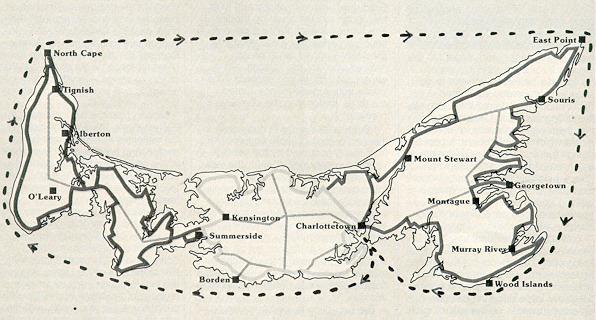

Not easy to reach by yacht, but quite accessible by plane, bus or car ferry, Prince Edward Island's shores are well worth exploring.

It is still a place where one can buy handmade woolen socks comprising the fleece of local sheep, stained glass fired in local kilns from local sands, and pottery thrown from local clays. It is a place whose gentle rolling hills provide —with the help of caring farmers —most of Canada's potatoes, and whose clear coastal waters give ready birth to the sweetest, tenderest of lobsters. It is a place whose land —nearly 70 percent of it under cultivation —has not been corrupted by oil refineries, steel mills and sprawling factories. It is a place whose only city — if it may be called such —has a population of only 15,000; and whose total population is only 125,000, most of whom leave their doors unlocked. It is a place —in contrast to the rest of the modern world —where entropy increases very slowly and the energy of life is not sapped by crime, traffic or heavy machinery.

And Prince Edward Island is a place where a sailor can find many a lonely anchorage —in a quiet bay or up a lazy river —and be watched only by inquisitive blue herons, beavers and seals.

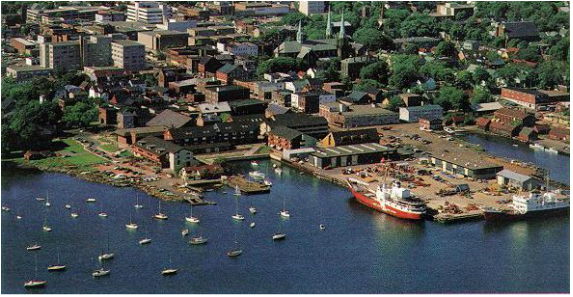

But, one wonders just how long the island can remain so untouched. Plans are afoot for new marina development. Charlottetown, the capital, is having its waterfront improved by the Hilton chain. Already, when the wind blows fresh from the south, base industrial fragrances cross the 20-mile Northumberland Strait from Pictou, Nova Scotia, and taint the sweet airs. And in 1984 PEI will host the finish of the final race in the Challenge Canada series, which will bring a congress of yachts from all over Canada and the U.S. to participate in Quebec's 450th anniversary. The idyll of PEI may have few stanzas to run.

It is still a place where one can buy handmade woolen socks comprising the fleece of local sheep, stained glass fired in local kilns from local sands, and pottery thrown from local clays. It is a place whose gentle rolling hills provide —with the help of caring farmers —most of Canada's potatoes, and whose clear coastal waters give ready birth to the sweetest, tenderest of lobsters. It is a place whose land —nearly 70 percent of it under cultivation —has not been corrupted by oil refineries, steel mills and sprawling factories. It is a place whose only city — if it may be called such —has a population of only 15,000; and whose total population is only 125,000, most of whom leave their doors unlocked. It is a place —in contrast to the rest of the modern world —where entropy increases very slowly and the energy of life is not sapped by crime, traffic or heavy machinery.

And Prince Edward Island is a place where a sailor can find many a lonely anchorage —in a quiet bay or up a lazy river —and be watched only by inquisitive blue herons, beavers and seals.

But, one wonders just how long the island can remain so untouched. Plans are afoot for new marina development. Charlottetown, the capital, is having its waterfront improved by the Hilton chain. Already, when the wind blows fresh from the south, base industrial fragrances cross the 20-mile Northumberland Strait from Pictou, Nova Scotia, and taint the sweet airs. And in 1984 PEI will host the finish of the final race in the Challenge Canada series, which will bring a congress of yachts from all over Canada and the U.S. to participate in Quebec's 450th anniversary. The idyll of PEI may have few stanzas to run.

But there is good reason why Challenge Canada culminates on Prince Edward Island — other than the tourism promoters' professional urge to bring yachtsmen ashore for souvenirs, entertainment, Malpeque Bay oysters and lobster suppers. It is that PEI is one of the most tempting sailing grounds in the Canadian Maritimes, and every sailor should have his day in the sun there.

PEI is blessed, in the summer, with mild temperatures, good winds and swimmable waters —the warm Gulf of St. Lawrence brushes the island and keeps things just right. There are harbors —most along the eastern and southern shores —where a yacht can choose between coming alongside in a aquiet fishing village (even alongside a quiet seafood place) or drop a hook under tall pines or in the lee of red sandstone bluffs. There are natural harbors and those protected by breakwaters. And PEI harbors, as yet, are never crowded.

I came to Prince Edward Island last July, despite my having declined an invitation to sail in the fourth annual Round The Island Race. I reasoned that there was a better way to see PEI, so I had asked the folks at the Department of Tourism, Industry and Energy where I might charter a yacht instead. Miss Diane Houston of the Department telephoned me that there were no charter yachts on PEI except an old wooden schooner that hauled tourists for day trips out of Victoria. Not what I had in mind. Miss Houston tried again.

This time she called the Charlottetown Yacht Club and asked, point blank, if anyobody wanted to take a Yachting editor out for a day or two. Two families volunteered. Others were willing, but hadn't the time.

At the moment I recognized that PEI's greatest resource —far above its potatoes, lobsters, quiet bays and lazy rivers —is its people. It is a fact that no visitor can ever forget.

The busy Charlottetown Yacht Club contrasts sharply with the red-cliffed coast of Cavendish, to the north. (Photo by Tourism PEI)On arrival at PEI's tiny jetport I went immediately to the Yacht Club to mingle with the crews and skippers of the Round The Island Race and get some flavor for my Yachting report on the race. My host, Ron White, of the race committee, introduced me around. That evening I partook of the first of several "lobster suppers" for which PEI is justly famous. They come in small, medium, and all-you-can-eat; I chose the middlin' route to satiety, then retired to a hotel on the island's east end, at Brudenell.

Early next morning I met Chris Brittain, of Veterans Affairs Canada. His family and some friends, the Mills, all on holiday, awaited me on two small cruising sailboats. After coffee and introductions, we slipped our moorings and headed out to Cardigan Bay and the craggy east coast. We sailed first past long rows of small floats lining the fairway like airport runway lights — oystermen's nets. They are apparently as effective as the laws that stritly govern PEI's seafood catch and keep the waters well stocked.

With the breeze up, we beat down the bay, past the small village of Georgetown, then poked our bow into St. Mary Bay, which Chris rightly described as one of the island's most peaceful, pretty and protected anchorages ( the author's alliteration). From there we sailed around Panmure Island, down the coast and inside Bear Point, PEI's southeast corner. Behind a mile-long sandbar lay Murray Harbor and its little complex of feeder rivers. Now, rivers in PEI are never mighty; they are placid tidal streams generally fed by small fresh-water creeks. As such, they make easy anchorages by day, and pleasant spots for overnight.

We chose to motor up the Greek River for lunch. The river gets its name not from Athens but from one of two Micmac Indian words: Kuhtowedek (reverberating echo) or Giotogoeteg (surrounding). (The Micmacs, who are now only four percent of PEI's populace, were its sole occupiers until the French and English reached its shores). At anchor we were alone, save for blue herons wading in the shoreside overhang. They ignored us.

After lunch we worked our way gently up the Murray River where we moored the boats off the home of Mr. Mills's sister and were driven back to Brudenell for, yes, a lobster supper.

Back at the yacht club in the morning, I joined the local press and television crowd in time to learn that the press boat's diesel wouldn't turn over in time for the start of the Round-the-Island Race. No matter. PEI's prime resource was again called to action and another local boat and owner were "pressed" into service. Writers, editors, videomen and photographers climbed aboard and met the start in a fresh southerly under a brilliant photogenic sky.

Once the fleet had cleared the harbor I joined my second voluntary hosts, John and Paula Dennis, aboard their beautiful homebuilt 45' ketch. They had just returned from a winter of sailing her in the Caribean sun, but were nonetheless willing to take a stranger for a cruise. We set our courses immediately to the west.

PEI is naturally divided into three segments; the middle one, Prince County (Actually the middle one is Queens County — J.E.), is bracketed by the two principal towns — Charlottetown to the east and Summerside to the west. Between them the coast typifies PEI at its best. Alongshore one passes under rich red cliffs that contrast sharply with a variety of greens and golds provided by the fields ad forests above them, PEI farmers grow vast tracts of wheat, oats and barley on the broads that border on the cliffs, and on a breezy, sunlit afternoon the wind rolls across the fields forming mutlihued waves that seem as extensions of the ocean waves that break on the strand below.

Paula, John and I sailed lazily to the west and in the late afternoon pulled into Victoria harbor where we tied up to the bulkhead of a local eatery. The only boats in the harbor were the schooner mentioned above, a small sloop and an aluminum hull under construction. It was high season.

After a pleasant dinner aboard we visited with some friends of the Dennis's — islanders, like Greeks, know somone everywhere. Then we explored the tiny town of Victoria, which is little more than a trio of antique shops and some barking dogs, but oh so charming. In the morning, we set sail for Summerside.

The breeze was light so we motorsailed and exchanged sea stories as though old friends. The Dennis' have a dream of sailing to far-off places, and they look upon their Caribbean venture as prelude. In the meantime they spend the summer season aboard their boat, which they have appointed as no other below. Dark woods, bits of stained glass, elegant cabinetry, brass fittings and lamps, merrily crammed bookcases, bright comforters, even dinnerware and glasses all blend to make a home within a hull.

Our one moment of excitement came with a sudden rain squall which passed quickly and left a rainbow to pierce the heart of a farmhouse perched on the bluffs above Sevenmile Bay. Even the rain god smiles on Prince Edward Island.

Summerside, in contrast to Victoria, has a bustling harbor and full marina. As we limped in to a dock — one blade of our prop had mysteriously broken off — we were surrounded by dozens of preteens in various sailing and rowing vehicles taking safety instruction from the Canadian Red Cross. They deliberately swamped canoes and dinghies all about, and splashed with joy as they did so.

It was late in the afternoon, with little prospect of getting a puller to remove the broken prop. But, once again the PEI resource was called into play. John called a friend on the other end of the island — a mechanic who worked as a night watchman — and he volunteered to bring a puller and his diving gear before breakfast the next day. We went off for a lobster supper. I ordered steak.

Though the prop was replaced as promised, I had no time to continue the cruise and accepted a ride back to Charlottetown with the mechanic.

For the next few days I alternated visits to the yacht club to check on the progress of the race, with scenic drives about the island. PEI reveals itself fully when one has a chance to sail around it and then cut across it by auto. The roads are efficient and there are more kilometers per capita in PEI than any other Canadian province. They are lined with modest government signs pointing out restaurants, craft shops and other touristic attractions. and the roadways have been laid out to take the driver through every corner of the island, inhabited or not.

By the time the famous Liar's Night arrived (in which the losers of the race must invent outrageous excuses for not being first on corrected time) I had seen the island's shell and heart, discovered its apparent beauties, and perhaps begun to know its wonderful people. It is a place not easily reached by yacht — there are no convenient charter services, so you either have to sail up on your own or from Nova Scotia, or get to know someone there with a boat. The last is not difficult to accomplish

Prince Edward Island is one of the few sailing places left in this complex world which promises and delivers the full pleasures of yachting. As the islanders say to all outsiders, when you come to Prince Edward Island you "come in from away."

To PEI the rest of the world is "away." The rest of the world has glass and steel skyscrapers, smoke stacks and gridlock. PEI has none. Social psychologists have done several studies on the children of PEI who seem to grow up surprisingly healthy and mentally fit. PEI is simply a place that works.

To know that it works one need only sail under those rugged red bluffs of an evening and watch the waving gold wheat fields, then smell the fresh biscuits in the morning.

PEI is blessed, in the summer, with mild temperatures, good winds and swimmable waters —the warm Gulf of St. Lawrence brushes the island and keeps things just right. There are harbors —most along the eastern and southern shores —where a yacht can choose between coming alongside in a aquiet fishing village (even alongside a quiet seafood place) or drop a hook under tall pines or in the lee of red sandstone bluffs. There are natural harbors and those protected by breakwaters. And PEI harbors, as yet, are never crowded.

I came to Prince Edward Island last July, despite my having declined an invitation to sail in the fourth annual Round The Island Race. I reasoned that there was a better way to see PEI, so I had asked the folks at the Department of Tourism, Industry and Energy where I might charter a yacht instead. Miss Diane Houston of the Department telephoned me that there were no charter yachts on PEI except an old wooden schooner that hauled tourists for day trips out of Victoria. Not what I had in mind. Miss Houston tried again.

This time she called the Charlottetown Yacht Club and asked, point blank, if anyobody wanted to take a Yachting editor out for a day or two. Two families volunteered. Others were willing, but hadn't the time.

At the moment I recognized that PEI's greatest resource —far above its potatoes, lobsters, quiet bays and lazy rivers —is its people. It is a fact that no visitor can ever forget.

The busy Charlottetown Yacht Club contrasts sharply with the red-cliffed coast of Cavendish, to the north. (Photo by Tourism PEI)On arrival at PEI's tiny jetport I went immediately to the Yacht Club to mingle with the crews and skippers of the Round The Island Race and get some flavor for my Yachting report on the race. My host, Ron White, of the race committee, introduced me around. That evening I partook of the first of several "lobster suppers" for which PEI is justly famous. They come in small, medium, and all-you-can-eat; I chose the middlin' route to satiety, then retired to a hotel on the island's east end, at Brudenell.

Early next morning I met Chris Brittain, of Veterans Affairs Canada. His family and some friends, the Mills, all on holiday, awaited me on two small cruising sailboats. After coffee and introductions, we slipped our moorings and headed out to Cardigan Bay and the craggy east coast. We sailed first past long rows of small floats lining the fairway like airport runway lights — oystermen's nets. They are apparently as effective as the laws that stritly govern PEI's seafood catch and keep the waters well stocked.

With the breeze up, we beat down the bay, past the small village of Georgetown, then poked our bow into St. Mary Bay, which Chris rightly described as one of the island's most peaceful, pretty and protected anchorages ( the author's alliteration). From there we sailed around Panmure Island, down the coast and inside Bear Point, PEI's southeast corner. Behind a mile-long sandbar lay Murray Harbor and its little complex of feeder rivers. Now, rivers in PEI are never mighty; they are placid tidal streams generally fed by small fresh-water creeks. As such, they make easy anchorages by day, and pleasant spots for overnight.

We chose to motor up the Greek River for lunch. The river gets its name not from Athens but from one of two Micmac Indian words: Kuhtowedek (reverberating echo) or Giotogoeteg (surrounding). (The Micmacs, who are now only four percent of PEI's populace, were its sole occupiers until the French and English reached its shores). At anchor we were alone, save for blue herons wading in the shoreside overhang. They ignored us.

After lunch we worked our way gently up the Murray River where we moored the boats off the home of Mr. Mills's sister and were driven back to Brudenell for, yes, a lobster supper.

Back at the yacht club in the morning, I joined the local press and television crowd in time to learn that the press boat's diesel wouldn't turn over in time for the start of the Round-the-Island Race. No matter. PEI's prime resource was again called to action and another local boat and owner were "pressed" into service. Writers, editors, videomen and photographers climbed aboard and met the start in a fresh southerly under a brilliant photogenic sky.

Once the fleet had cleared the harbor I joined my second voluntary hosts, John and Paula Dennis, aboard their beautiful homebuilt 45' ketch. They had just returned from a winter of sailing her in the Caribean sun, but were nonetheless willing to take a stranger for a cruise. We set our courses immediately to the west.

PEI is naturally divided into three segments; the middle one, Prince County (Actually the middle one is Queens County — J.E.), is bracketed by the two principal towns — Charlottetown to the east and Summerside to the west. Between them the coast typifies PEI at its best. Alongshore one passes under rich red cliffs that contrast sharply with a variety of greens and golds provided by the fields ad forests above them, PEI farmers grow vast tracts of wheat, oats and barley on the broads that border on the cliffs, and on a breezy, sunlit afternoon the wind rolls across the fields forming mutlihued waves that seem as extensions of the ocean waves that break on the strand below.

Paula, John and I sailed lazily to the west and in the late afternoon pulled into Victoria harbor where we tied up to the bulkhead of a local eatery. The only boats in the harbor were the schooner mentioned above, a small sloop and an aluminum hull under construction. It was high season.

After a pleasant dinner aboard we visited with some friends of the Dennis's — islanders, like Greeks, know somone everywhere. Then we explored the tiny town of Victoria, which is little more than a trio of antique shops and some barking dogs, but oh so charming. In the morning, we set sail for Summerside.

The breeze was light so we motorsailed and exchanged sea stories as though old friends. The Dennis' have a dream of sailing to far-off places, and they look upon their Caribbean venture as prelude. In the meantime they spend the summer season aboard their boat, which they have appointed as no other below. Dark woods, bits of stained glass, elegant cabinetry, brass fittings and lamps, merrily crammed bookcases, bright comforters, even dinnerware and glasses all blend to make a home within a hull.

Our one moment of excitement came with a sudden rain squall which passed quickly and left a rainbow to pierce the heart of a farmhouse perched on the bluffs above Sevenmile Bay. Even the rain god smiles on Prince Edward Island.

Summerside, in contrast to Victoria, has a bustling harbor and full marina. As we limped in to a dock — one blade of our prop had mysteriously broken off — we were surrounded by dozens of preteens in various sailing and rowing vehicles taking safety instruction from the Canadian Red Cross. They deliberately swamped canoes and dinghies all about, and splashed with joy as they did so.

It was late in the afternoon, with little prospect of getting a puller to remove the broken prop. But, once again the PEI resource was called into play. John called a friend on the other end of the island — a mechanic who worked as a night watchman — and he volunteered to bring a puller and his diving gear before breakfast the next day. We went off for a lobster supper. I ordered steak.

Though the prop was replaced as promised, I had no time to continue the cruise and accepted a ride back to Charlottetown with the mechanic.

For the next few days I alternated visits to the yacht club to check on the progress of the race, with scenic drives about the island. PEI reveals itself fully when one has a chance to sail around it and then cut across it by auto. The roads are efficient and there are more kilometers per capita in PEI than any other Canadian province. They are lined with modest government signs pointing out restaurants, craft shops and other touristic attractions. and the roadways have been laid out to take the driver through every corner of the island, inhabited or not.

By the time the famous Liar's Night arrived (in which the losers of the race must invent outrageous excuses for not being first on corrected time) I had seen the island's shell and heart, discovered its apparent beauties, and perhaps begun to know its wonderful people. It is a place not easily reached by yacht — there are no convenient charter services, so you either have to sail up on your own or from Nova Scotia, or get to know someone there with a boat. The last is not difficult to accomplish

Prince Edward Island is one of the few sailing places left in this complex world which promises and delivers the full pleasures of yachting. As the islanders say to all outsiders, when you come to Prince Edward Island you "come in from away."

To PEI the rest of the world is "away." The rest of the world has glass and steel skyscrapers, smoke stacks and gridlock. PEI has none. Social psychologists have done several studies on the children of PEI who seem to grow up surprisingly healthy and mentally fit. PEI is simply a place that works.

To know that it works one need only sail under those rugged red bluffs of an evening and watch the waving gold wheat fields, then smell the fresh biscuits in the morning.

RACING YACHTSMAN

The Month in Yachting, (October 1982 J.A.S.)

A TOUGH COURSE PROMISES MAJOR OCEAN RACING EVENT

Prince Edward Island, Canada, July 30 — The Round Prince Edward Island Race (RPEIR) will some day be a major offshore IOR event. As of the present, it is not.

The unusually challenging 350-mile race, in its fourth year, is fraught with changeable weather and swift tidal currents and eddies, and it demands concentration and local knowledge. And for racers who glance to starboard during the clockwise circumnavigation, it is a splendid tour of waving green wheat fields, dramatic red cliffs, and picuresque towns on one of nature's great creations — an island rich in beauty and charm and as yet unspoiled by man.

The 1982 13-boat race was won, for the second year in a row, by Chene Flyer, a C&C 29 from Shediac, New Brunswick. According to her enthusiastic crew and owner/skipper, Doug Inglis, she won on tenacity smart tactics, and the fearless but skillful flying of a spinnaker in 45-knot winds when most of the other yachts shortened sail and three sought harbors of refuge.

But the real "story" of the 1982 RPEIR came at the post-race dinner, called "Liar's Night," when the losers all make their excuses for not winning. For example, one yacht's navigator claimed to have lost because he had been cautioned not to round a mark — a red flasher — until it turned green. The delay allowed the fleet to pass. On a second yacht two crewmen became helplessly lodged in the companionway during a watch change, trapping the watch below until the backstay could be cranked up to spring open the companionway. On another, the crew all put two anti-seasickness patches behind their ears and fell into a collective hallucinatory stupor which required the skipper to singlehand the race.

The RPEIR and Liar's Night were the invention of Alan Holman, a local radio man, who convinced the Charlottetown Yacht Club to sponsor the race after he cruised the course and deemed it "safe."

The first race, in 1979, had eight entries from 26' to 42'. On the first night, however, a storm battered the fleet and all but Holman, on his Contessa 26, retired into Summerside, about 50 miles from the start. Holman, still determined to make a race, forced his crew to plow on and, including a manditory six-hour layover, finished in 79 hours. He then challenged the drop-outs to justify thieir quitting, demanding that their explanations be good. Thus Liar's Night became a post-race tradition.

This year's race was an equally tough one. After a brisk start at 12:30 on Monday, July 26, and a brief spinnaker reach, the airs went light and on the nose as the fleet, ranging from 22' to 43', worked the island's south shore against a foul tide. Few made it to North Point by Tuesday morning, and all yachts were intermittently becalmed along the 95-mile open stretch to East Point.

But by late Wednesday a cold front, underestimated by meteorologists, kicked up a gale-force southerly and steep seas in the opposing current — the third gale to visit the race in four years.

By Thursday at 1030, after a tough slog in winds exceeding 50 knots, only three yachts had finished --Windancer (a local C&C 34), Chene Flyer, and (yes) Windancer (a Mason 43 owned by Barry Himmelman of San Diego, but sailed out of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia). Several yachts were still beating into increasing winds along the eastern shore; and despite Canadian Air Force spotter planes and Coast Guard observers, three yachts remained unaccounted for until the skies cleared and visibility improved at midday Friday.

At 1900 on Friday, though six yachts had not yet finished, Liar's Night commenced with drinks and dinner for about 100 people. But the dinner was interrupted by the finish of Compromise Too (a Shark 24) and Razzmatazz ( a Tanzer 22), whose survival was celebrated by flares and horns as the assemblage left dessert and coffee to welcome their heroes to the yacht club wharf. Swept into the event, the bearded skippers immediately joined in the lies. The Shark lost because it circumnavigated twice; the Tanzer lost because the shark crew, while cresting a nearby wave, snatched the windvane and VHF antenna from her mast.

Another yacht's spokesman claimed a delay to take bottom samples for an oil company seeking a better way to make French fries; still another blamed Poseidon on a sailboard.

But, though Liar's Night was a bawdy banquet of the beaten, which left the island in a happy shambles, there is serious consideration to be given the RPEIR as an important addition to the racing calendar.

Prince Edward Island has the potential of giving well-founded yachts with experienced crews a magnificent ocean race. The distance, conditions and landscape should please all manner of competitors. But the Charlottetown Yacht Club, for all its efforts, has not yet organized the race to take advantage of the challenge, and has allowed the race to remain an essentially local event, raced only under PHRF ratings, and with inadequate attention to regulations and safety. (Liferafts and EPIRBS are not required, and the Shark was allowed to race despite her lack of required stantioned lifelines).

After the race a new spirit invaded the race committee (headed by Ron White), inspired perhaps by the many people who worried about the yachts during the storm. The committee — recognizing the need for better organization, stricter safety enforcement, a significant feeder race and an IOR division — has already begun preparations for 1983 and 1984. In 1984 a series of challenge races among the 10 Canadian provinces will finish in Prince Edward Island. Raced in a new class being designed by C&C, but open to all yachts, the series will afford Prince Edward Island an excellent opportunity for a large competitive Round The Island fleet, and convert the local fun race into a premier event.

After the race, the harbors and bays of Prince Edward Island will beckon tired sailors for some easy cruising to replenish their energies. And the people of Prince Edward Island will undoubtedly make them feel at home. J.A.S.

From the Readers — October 1982

Safety precautions for offshoreYour article on the Round Prince Edward Island Race (October, page 143) was well written, infromative and for the most part, accurate. As the owner and skipper of the Shark sailboatCompromise II referred to in the article, however, I was disturbed by the implication that the boat was less than safe because she was not equipped with stanchioned lifelines. The boat was, in fact, equipped with a continuous lifeline along each side deck so that a crewman could attach his safety harness to the line before he left the cokpit. These lines satisfied the racing rules requirements. In addtion, pad eyes through-bolted to the companionway bulkhead permitted a safety harness to be clipped on before the creman left the cabin.

There are many experienced sailors who believe that reliance on stanchioned lifelines can be hazardous and that the safety of the crew can be better provided for by other means. In addition to the lifelines referred to above, this particular Shark has wooden handrails along the coach roof and along the deck forward of the mast on each side, as well as a bow pulpit. The boat was well prepared from a safety standpoint. I doubt that any experienced sailor would take a boat offshore in an ocean race of this type without such preparation.

Robert Griffith

Scarborough, Ont.

Mr Griffith is quite correct when he says that his Shark was equipped for offshore work; and I commend him and his crew (which included our colleague from Sailing Canada magazine, Richard Holmes) for toughing out a tough race. In discussions we all had with the Race Committee, as represented by Ron White, it was generally agreed, however, that the spirit, if not the letter of the race circular specified stanchioned lifelines. While I personally agree that a yacht as small as a Shark (24') does not gain necessarily from these devices, I respect the committee's intentions. The conclusion that we came to , at the Charlottetown Yacht Club, was that future races should have a small-boat division for yachts without inboard engines ( and other qualifications), such as our MORC yachts. — J.A.S.

A TOUGH COURSE PROMISES MAJOR OCEAN RACING EVENT

Prince Edward Island, Canada, July 30 — The Round Prince Edward Island Race (RPEIR) will some day be a major offshore IOR event. As of the present, it is not.

The unusually challenging 350-mile race, in its fourth year, is fraught with changeable weather and swift tidal currents and eddies, and it demands concentration and local knowledge. And for racers who glance to starboard during the clockwise circumnavigation, it is a splendid tour of waving green wheat fields, dramatic red cliffs, and picuresque towns on one of nature's great creations — an island rich in beauty and charm and as yet unspoiled by man.

The 1982 13-boat race was won, for the second year in a row, by Chene Flyer, a C&C 29 from Shediac, New Brunswick. According to her enthusiastic crew and owner/skipper, Doug Inglis, she won on tenacity smart tactics, and the fearless but skillful flying of a spinnaker in 45-knot winds when most of the other yachts shortened sail and three sought harbors of refuge.

But the real "story" of the 1982 RPEIR came at the post-race dinner, called "Liar's Night," when the losers all make their excuses for not winning. For example, one yacht's navigator claimed to have lost because he had been cautioned not to round a mark — a red flasher — until it turned green. The delay allowed the fleet to pass. On a second yacht two crewmen became helplessly lodged in the companionway during a watch change, trapping the watch below until the backstay could be cranked up to spring open the companionway. On another, the crew all put two anti-seasickness patches behind their ears and fell into a collective hallucinatory stupor which required the skipper to singlehand the race.

The RPEIR and Liar's Night were the invention of Alan Holman, a local radio man, who convinced the Charlottetown Yacht Club to sponsor the race after he cruised the course and deemed it "safe."

The first race, in 1979, had eight entries from 26' to 42'. On the first night, however, a storm battered the fleet and all but Holman, on his Contessa 26, retired into Summerside, about 50 miles from the start. Holman, still determined to make a race, forced his crew to plow on and, including a manditory six-hour layover, finished in 79 hours. He then challenged the drop-outs to justify thieir quitting, demanding that their explanations be good. Thus Liar's Night became a post-race tradition.

This year's race was an equally tough one. After a brisk start at 12:30 on Monday, July 26, and a brief spinnaker reach, the airs went light and on the nose as the fleet, ranging from 22' to 43', worked the island's south shore against a foul tide. Few made it to North Point by Tuesday morning, and all yachts were intermittently becalmed along the 95-mile open stretch to East Point.

But by late Wednesday a cold front, underestimated by meteorologists, kicked up a gale-force southerly and steep seas in the opposing current — the third gale to visit the race in four years.

By Thursday at 1030, after a tough slog in winds exceeding 50 knots, only three yachts had finished --Windancer (a local C&C 34), Chene Flyer, and (yes) Windancer (a Mason 43 owned by Barry Himmelman of San Diego, but sailed out of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia). Several yachts were still beating into increasing winds along the eastern shore; and despite Canadian Air Force spotter planes and Coast Guard observers, three yachts remained unaccounted for until the skies cleared and visibility improved at midday Friday.

At 1900 on Friday, though six yachts had not yet finished, Liar's Night commenced with drinks and dinner for about 100 people. But the dinner was interrupted by the finish of Compromise Too (a Shark 24) and Razzmatazz ( a Tanzer 22), whose survival was celebrated by flares and horns as the assemblage left dessert and coffee to welcome their heroes to the yacht club wharf. Swept into the event, the bearded skippers immediately joined in the lies. The Shark lost because it circumnavigated twice; the Tanzer lost because the shark crew, while cresting a nearby wave, snatched the windvane and VHF antenna from her mast.

Another yacht's spokesman claimed a delay to take bottom samples for an oil company seeking a better way to make French fries; still another blamed Poseidon on a sailboard.

But, though Liar's Night was a bawdy banquet of the beaten, which left the island in a happy shambles, there is serious consideration to be given the RPEIR as an important addition to the racing calendar.

Prince Edward Island has the potential of giving well-founded yachts with experienced crews a magnificent ocean race. The distance, conditions and landscape should please all manner of competitors. But the Charlottetown Yacht Club, for all its efforts, has not yet organized the race to take advantage of the challenge, and has allowed the race to remain an essentially local event, raced only under PHRF ratings, and with inadequate attention to regulations and safety. (Liferafts and EPIRBS are not required, and the Shark was allowed to race despite her lack of required stantioned lifelines).

After the race a new spirit invaded the race committee (headed by Ron White), inspired perhaps by the many people who worried about the yachts during the storm. The committee — recognizing the need for better organization, stricter safety enforcement, a significant feeder race and an IOR division — has already begun preparations for 1983 and 1984. In 1984 a series of challenge races among the 10 Canadian provinces will finish in Prince Edward Island. Raced in a new class being designed by C&C, but open to all yachts, the series will afford Prince Edward Island an excellent opportunity for a large competitive Round The Island fleet, and convert the local fun race into a premier event.

After the race, the harbors and bays of Prince Edward Island will beckon tired sailors for some easy cruising to replenish their energies. And the people of Prince Edward Island will undoubtedly make them feel at home. J.A.S.

From the Readers — October 1982

Safety precautions for offshoreYour article on the Round Prince Edward Island Race (October, page 143) was well written, infromative and for the most part, accurate. As the owner and skipper of the Shark sailboatCompromise II referred to in the article, however, I was disturbed by the implication that the boat was less than safe because she was not equipped with stanchioned lifelines. The boat was, in fact, equipped with a continuous lifeline along each side deck so that a crewman could attach his safety harness to the line before he left the cokpit. These lines satisfied the racing rules requirements. In addtion, pad eyes through-bolted to the companionway bulkhead permitted a safety harness to be clipped on before the creman left the cabin.

There are many experienced sailors who believe that reliance on stanchioned lifelines can be hazardous and that the safety of the crew can be better provided for by other means. In addition to the lifelines referred to above, this particular Shark has wooden handrails along the coach roof and along the deck forward of the mast on each side, as well as a bow pulpit. The boat was well prepared from a safety standpoint. I doubt that any experienced sailor would take a boat offshore in an ocean race of this type without such preparation.

Robert Griffith

Scarborough, Ont.

Mr Griffith is quite correct when he says that his Shark was equipped for offshore work; and I commend him and his crew (which included our colleague from Sailing Canada magazine, Richard Holmes) for toughing out a tough race. In discussions we all had with the Race Committee, as represented by Ron White, it was generally agreed, however, that the spirit, if not the letter of the race circular specified stanchioned lifelines. While I personally agree that a yacht as small as a Shark (24') does not gain necessarily from these devices, I respect the committee's intentions. The conclusion that we came to , at the Charlottetown Yacht Club, was that future races should have a small-boat division for yachts without inboard engines ( and other qualifications), such as our MORC yachts. — J.A.S.

Yachting MagazineI would like to take this opportunity to thank Charles Barthold and Ken Wooten of Yachting Magazine for their support and blessings on using the following article from their magazine. Yachting Magazine can be found on the World Wide Web.

|

Awards• Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

• Consectetur adipiscing elit • Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet • Consectetur adipiscing elit |

Publications• Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet

• Consectetur adipiscing elit • Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet • Consectetur adipiscing elit |